This is the true story of what happened when all the trauma was supposed to be over, when I left my “home” on the park bench on the outskirts of Salt Lake City for the last time in 2017. People like to call this transitional period an “emergence,” lending a triumphal note to the narrative—the unhoused person escaping a disturbing chrysalis to become a fuller and better human, new-winged and free.

But that’s not my story.

My story is about how the pain continued into the healing, morphing from something blatant and socially distasteful into something socially acceptable. I spent two years in homelessness, 442 days in a filthy, noisy, violence-filled shelter, the other 260 in spaces that included a dark room in which I was repeatedly held hostage by a man who beat and sexually assaulted me; public libraries where other men grabbed my breasts; and the brightly lit confines of jail cells and psych wards, where officials locked me up after those assaults. That’s when the assaults became official: police frisking my breasts, crotch, and anus; stern doctors injecting me against my will with antipsychotics that only further separated me from my own mind and body.

My life since has included a series of quieter violations, each still dehumanizing in its own way—but all essentially authorized as part of the way America addresses its “homelessness problem,” a construct largely created by liberals responding to Reagan-era welfare politics.

Thus, to be formerly unhoused is to be the subject of continual scrutiny, stuck in a system that relies on acts of individual kindness and moral surveillance meant to ensure the recipient of other people’s generosity remains “deserving” of it.

And so that’s what I emerged into: a wall of judgment that has made it much harder to reconstitute my own identity beyond what you perceive to be that of a “damaged” and struggling person, one hobbled by the character defects you assume I have, that to reenter the privileges of middle-class life would become an inconceivably herculean task.

“You were homeless?” people like you have often said to me, as if in disbelief that someone so like themselves could ever tumble to the bottom rungs of society.

Yes. I was once, perhaps, a lot like you—college-educated, successful in my professional pursuits, first in journalism and then in business, a home and horse owner. I do not make my accusations lightly. I know that when I point my finger at you, I also point it toward the version of me that hailed from the same belief system.

You patronized me. Told me I was your “project.” Told me you couldn’t pay me properly because I came from “an unstable background.”

I had become a leper whose life you decided was worth saving but whose character was now permanently in question. Yes, you would give me “gifts.” But in exchange, I was required to be grateful, docile, never angry.

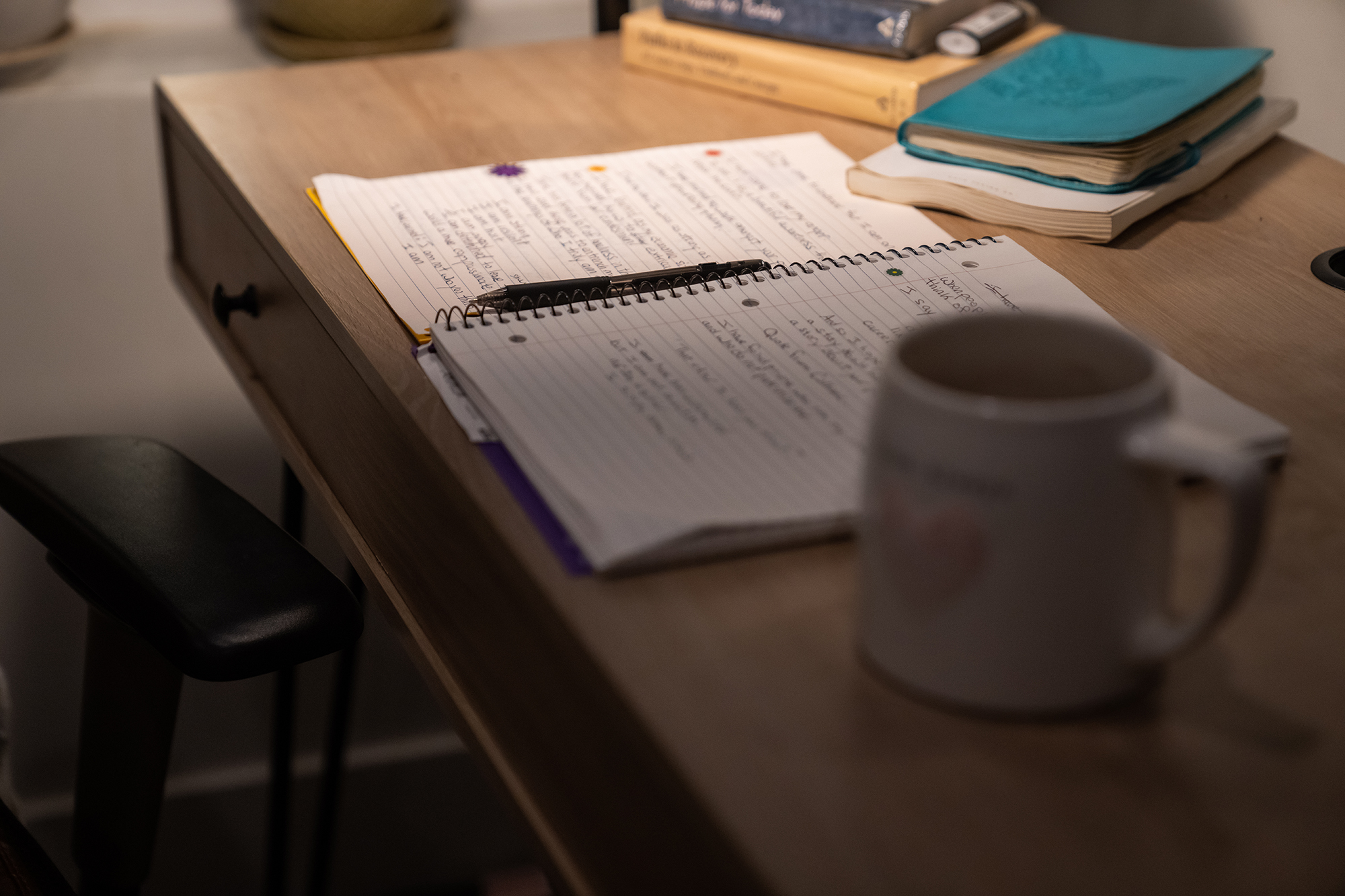

Here, let me show you. Walk with me through my “emergence.”

On my last day on that park bench, I couldn’t see a foot in front of me. I had lost my glasses and had no money to replace them. The snow, the tall oak trees around my park bench, the flowers I’d picked from street shrubberies and people’s yards in an attempt to decorate my “home”—everything was a blur.

It was the first week of May, a weekday, though I cannot remember which one, as the days were running monotonously together. I was curled up on that bench, swaddled in every piece of clothing I had. But I was so cold I was shaking again.

There was nothing about the day I wanted to face—not walking up to the food pantry window and hoping that the volunteers would have coffee. Not asking a volunteer behind the barred window for another bar of soap and as many cups of hot water as I could carry. All the regular volunteers openly complained about the number of foam cups I asked for.

“What do you need all this for?” they would ask, their voices full of suspicion. “You’re wasting cups.”

I never explained, just took what I could get.

Then I would walk across the church’s pavilion, past the bathrooms locked to the homeless, past the water fountain with the pretty blue basin, up the steep concrete stairs, and into the small, rectangular grass yard. There, I would crouch with my back against the wall and wash my underarms and then genitals, carefully dipping my tiny bar of soap into the hot water. If there was any extra water in my cup, I would spot-clean a T-shirt and hang it on one of the metal stubs jutting out of the concrete wall. I resented the sight of them. I wanted hangers in a closet. Would I ever have hangers in a closet again?

The worst moments of these endlessly circuitous days: when my body warned me that it was time to have a bowel movement.

My intestines had become so inflamed from constant stress that I could no longer control them. I had less than a couple of minutes between the initial urge to defecate and the time when the overwhelming pressure surged through me. I would dash in and out of stores asking to use bathrooms but was usually told that they were reserved “for paying customers only.” So I would squat and drop my pants, hoping, praying, no one would see me.

Homelessness was a series of detachments—from society in general but also from my own person. Trauma rewires the mind as well as the body. On that morning in May, I knew with every cell of my being that if I did not leave homelessness, I would soon die. Either my assailant was going to stuff me in a body bag, as he had assured me he would someday, or I would succumb to the weather.

Slowly, methodically, I freed myself from my many layers of clothes: socks over socks, nylon stretch pants beneath jeans, sweaters and sweatshirts on top of T-shirts, and wool scarves wrapped around my midriff. Down to a pair of cargo pants and a sweatshirt, I sat up on the bench and searched the oaks and pale gray sky for guidance.

Nothing.

Then the vivid memory of my late father, a Black immigrant from Panama who came to America in the 1940s, graduated from a Black college, and worked as a microbiologist for nasa.

“When you don’t know what to do, just take a step in the direction you want to go,” he had told me when I was trying to decide what to major in at San Francisco State University. “Then take another step.”

His advice had served me well over the years. But on that park bench, I no longer had a penny to my name. No living relatives I felt I could turn to for help. Still, I packed my toiletries and clothes into my tiny backpack and a plastic garbage bag. I made my way through the blur of trees to a stream, near the spot where I had last been arrested for bathing. I quickly washed my face and brushed my teeth. Then I stepped onto the trails and then the streets that led into downtown Salt Lake City, wishing all the while that I could see a foot ahead of me.

Two miles later, I arrived at a regular breakfast offering in downtown Salt Lake City. Dozens of people stood outside in long lines in front of folding tables topped with large carafes of steaming coffee.

I recognized the dark-skinned woman wearing white knee-high socks and brown Birkenstocks held together with duct tape. She was known for standing on the edge of Liberty Park, lifting her head to the clouds, and singing hauntingly beautiful arias. I smiled at her, but she looked away.

I still remember her name, but I won’t mention it. Though my story is true and has been fact-checked, some of the names of people have been changed. Because individuals are not the focus here. Rather, I want you to see the collective consciousness created around those who experience homelessness, a cultural apparatus that you might find yourself unknowingly supporting.

A thin, middle-aged man with mottled skin and long ink-black hair—I’ll call him Robert—told me he was one of the volunteers and asked me what kind of donut I wanted.

“Chocolate,” I told him. He handed me two.

“How are you?” he asked, smiling broadly.

“I am looking for help,” I answered simply, reaching for a cup of coffee.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I had just taken my first steps into the American way of helping “the homeless.” And now that I’ve spent four years reporting on the nature of homelessness, I have some surprising facts to share with you.

Homelessness as we perceive it today was largely invented 40 years ago, when President Ronald Reagan dismantled federal funding for the poor—just as a recession took hold.

Yes, the number of people living on the streets grew, but the “increase in attention was totally out of proportion with the increase in the phenomenon,” wrote Mark Stern, an expert on the history of social welfare and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, in his 1984 paper “The Emergence of the Homeless as a Public Problem.”

In the early 1980s, the unhoused were garnering widespread and unprecedented attention; first, following the seminal 1979 case Callahan v. Carey, in which the city and the state of New York argued over which was obligated to care for homeless people. (A consent decree committed both to shared responsibility.) Newspapers in other cities began reporting on the homeless, in good and bad light. In 1981, the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote about local establishments complaining of unhoused men hurting business; that winter, national media devoted coverage for the first time to homeless people trying to survive the historically brutal freeze.

The unhoused “gained a new kind of ‘newsworthiness’ that made them accessible to a television audience,” Stern wrote.

And so, facing the Reagan cuts, liberals repositioned the war on poverty to be a war on homelessness.

Up until this point, “the homeless” were not a single category; distinct—though still derogatory—labels denoted different kinds of people. “Hobos” initially were itinerants traveling in search of work, for example; “tramps” were considered familyless wanderers. But the new war on homelessness changed that, collapsing all unhoused people into one monolithic category of helplessness.

“The plight of homeless people provided concrete, compelling images…that worked to arouse public concern,” then–UCLA law professor Lucie White wrote in her 1991 essay “Representing ‘The Real Deal.’” “Put bluntly, [advocates] identified ourselves with the cause of ‘homelessness’ because, in an adverse situation, we could not see any better strategic option.”

Thus, society created a new species of people, separate from “the poor,” with their own “distinct pathologies and special needs,” White wrote. And we carefully crafted an image of them: one of broken passivity and victimhood.

“We didn’t intend, through these efforts, to construct a new moral category of the poor, to impose a new stigma on already beleaguered people, or to introduce new divisions between them,” she wrote. “There simply seemed to be no better way, in the 1980’s, to picture the urgency of housing market failure and to give new luster to the very old struggles of the poor.”

In summation, she wrote: “The plight of the homeless seemed to offer an island of moral certainty.”

Almost 40 years later, I became the subject of that moral certainty. Which is where my anger comes in.

Artwork by Anthony Gerace; Photography by Niki Chan Wiley

Having been one of you for 50 years, I knew what these questions were doing. You were sussing me out, deciding whether I was among the deserving, the properly needy, whether I would own the idea that my misfortunes were in fact my “own” mistakes, agreeing to blame myself.

And so I answered, as I still answer:

Because my father had died in 2000 and left me enough money to quit a job at a paper getting ready to downsize. Because I was sure that the nonprofit I had created to help inner-city children write and perform their life stories would sustain me. Because when the grants we had received weren’t paying me or the rest of the staff enough to live on, I moved to Oregon and bought a 3-acre horse ranch. Because I love horses more than anything in this world, and I thought I could give them and myself happiness by building a business around them. Because, like millions of others in the middle of the Great Recession, I made stupid mistakes with money and credit cards and second mortgages.

Because, in that nightmarish year between 2013 and 2014, when I lost my home in a devastating house fire, risking my life to run into that burning building and yank the landlord out from it, when my mother was diagnosed with a terminal disease that she promptly died from, when every single family relationship I had fell apart, when my dog was also diagnosed with cancer, I could not think clearly. Because suddenly ostracized by my family—an estrangement that would worsen throughout my homelessness and my emergence—I froze.

I tried to sell my business and land new jobs. But there weren’t any takers. No one responded to my resumes.

When I was unable to pay the rent to a customer who had heard about the fire and invited me to live with her, she asked me to leave and sign over the ownership of my two horses to her. A notary came to her home to witness the transaction that suddenly and permanently ended a life that had become my identity. The next day, I euthanized and buried my beagle and said goodbye to my horses, whom I considered family.

And because after couchsurfing at the homes of friends, I finally landed in a homeless shelter in Salt Lake City. My mind continued to freeze, dammit. And that made me vulnerable to John, who was waiting for someone exactly like me to prey upon.

I met him while standing in line at the outreach center across the street from the shelter. He stepped away from his job staffing the front counter, bowed in a gentlemanly way, and offered me a pair of fleece-lined gloves. It was December and snowing, and I didn’t have a winter coat, let alone a pair of gloves. He introduced himself and told me that God wanted him to extend kindness to me.

Then he stood outside the doors of the women’s shelter every morning, waiting for me to emerge. His plan to control my life unfurled within a matter of weeks. First he walked me to the library, where I spent my days. Then he lent me his duffel bag after the clasp on my leather satchel broke, the last vestige from my old life. But John’s bag was too small to hold all my belongings, so he offered to keep my other things in his storage unit a few blocks from the shelter.

On a spring day in 2015, I entered the dimly lit rented unit to retrieve my belongings. John quickly pulled down the metal door and locked me inside with him. I told him I wanted to leave, but he blocked me. When I tried to shove him away, he grabbed me so tightly that he left black and blue marks on my arms. I was overwhelmed by fear and confusion. I remember John screaming vile things. I remember him overwhelming me physically to keep me from escaping. Every time I spoke out, the physical pain escalated. I don’t remember much else. Finally, John told me I could go and he rolled open the door. I asked a man on the street what day it was. Friday, he said. Two days had passed.

The abuse continued for an entire year.

A person in trauma does not choose among flight, fight, or freeze. The brain, in its attempt to save the body, regulates the nervous system in whatever way it needs to. I froze, a survival mechanism that, in the face of my bloodthirsty assailant, likely saved my life. And so I became “stuck” inside a terrorized nervous system, fixated on my moment-to-moment survival.

In fact, according to Thomas Hübl, co-author of the book Healing Collective Trauma: A Process for Integrating Our Intergenerational and Cultural Wounds, homelessness is a “strong trauma symptom,” not a sign of personal frailty.

And the trauma symptom that warns of the deepest pain? “Muteness,” he said.

Within weeks, I stopped talking, save for the words “yes” and “no” and when I gave my Social Security number to the police, who found me lying naked in the streets after the sexual assaults.

But all the ambulances and police did was usher me into other rooms I couldn’t escape.

Sometimes I was taken to jail, where the guards roughly frisked me, accused me of liking to take my clothes off, and threw me in a cell. Other times, when the jails were full, the police drove me to a psych ward, where my silence and passivity were reframed.

I had never before been diagnosed with any mental illness. But in homelessness, I was given a smorgasbord of misdiagnoses. Schizoaffective. Bipolar. Manic. Paranoid. I was injected with court-ordered antipsychotics to the point where I got so dizzy I couldn’t walk without holding on to the handrails alongside the hospital corridors.

I don’t want to give you any more details about my stays in various psych wards. To give you more details would be to further concretize that shattered image of Lori Yearwood—an image of a person who must continually fight to be treated as someone deserving of free agency.

I don’t want your pity. I want what you want: respect for having overcome adversity; acknowledgment that my accomplishments before homelessness were not wiped out in that state.

At the donut stand on that day in May when I walked away from my bench, Robert told me he worked with the same church that organized the weekday breakfasts. In fact, he drove the bus that took people back and forth between the donut stand and the church. Did I want to go? he asked.

“Yes,” I said, “okay.”

He blasted ’80s pop music while he drove. I sat across from him.

“You seem like an educated woman,” Robert said, looking over at me.

“I used to be a journalist,” I answered, remembering how I had styled my hair that morning by dunking my head in the river.

“Yeah?” Robert said. “Maybe you could work for Street News.”

The publication was a newspaper that homeless people sold on the streets, he said. “They’re always looking for stories.”

This exchange was one of the only real conversations I’d had in two years.

The church was located within a plain cement building. Inside, dozens of exhausted-looking people sat at tables, talking, eating, even sleeping, their slumped heads buried in their arms.

I followed Robert into yet another room with more food—chocolate bars and plastic containers of food that could be warmed in the microwave on the back countertop. Here, Robert introduced me to a short man with a beard and a wide smile, who ran Street News for the church.

“Lori is a journalist!” Robert boomed. “She wrote for the Miami Herald!”

The man shook my hand. “Great! We’ll put you to work! We need writers.”

“Really?” I blurted.

“Sure,” he said. I could start by writing a feature about homeless moms on Mother’s Day.

“Okay,” I said, trying to appear unfazed by the offer to be paid to write again.

That week, I spent my nights in an austere Christian rescue shelter that one of the pastors at the church had pointed me toward. There, I was reminded of my precarious position when I unknowingly broke a rule by asking a woman at a church outing if she knew anyone who might have a spare bedroom I could rent. That woman told the shelter manager about our conversation, and the shelter manager admonished me.

“You are not supposed to put the burden of your situation on the members of my church,” she told me. “It’s embarrassing.”

But I had no idea how to find a place to live, I told her.

“I’m sorry you’re in such a difficult position,” the woman responded. “You’ll probably have to go back to the city shelter.”

I will always look at what happened next as an ineffable grace. During that week, another pastor told me he felt strongly that I should contact an organization called Journey of Hope.

“The executive director there, she will help you,” he urged.

Within three days of meeting the executive director, she made me the “house mom” of a transitional home, a job for which I was given housing in return.

I wish I could tell you that was my happy ending. But homelessness is also about a state of mind that continues to be projected onto others, even those who have managed to escape its physical conditions.

Less than a week after leaving the park bench, I reported and wrote the story about unhoused mothers. I still couldn’t see much of anything, so I asked the head pastor, Pastor Scott, if he would give me money for eye contacts.

“How about if you earn them?” he asked. “Wouldn’t you feel better about that?” No, I wouldn’t, I wanted to say. But I was silent, doing what I needed to get the money for my contacts.

“We’re about supporting self-sufficiency here,” he said.

A tidal wave of shame and anger crashed through my body. I had been working since I was 12, when I offered myself up as a teacher’s example in beginning ballet classes so that I could take more advanced classes for free. I worked my way through college. As soon as I graduated with honors from San Francisco State University, I began working as a full-time reporter. Years later, determined to see my business succeed, I refused to take a single day off for more than eight years.

But as I stood meekly in front of that pastor, I swallowed my shame and repressed my anger. I needed his writing job more than I had ever needed any job in my life. And for that I needed his approval.

I couldn’t see the faces of the women I interviewed in the lunchroom of the church that day, but the story was published, and true to his word, the pastor drove me to an optometrist, where I was handed a box of contacts and a bottle of lens solution.

I can still see the newly paved, jet-black tar of that parking lot. I remember noticing, with a sad kind of shock, the outlines of the steel handles on the entrance doors of the store.

After that, I was told I could write up to two stories a month, for which I would be paid $200 each. I wrote more stories for yet another church in exchange for monthly bus passes. But I still couldn’t let my defenses down; the women in the transitional house struggled to make rent—this meant the house itself was under the continual threat of being shuttered.

Knowing the church was looking for a secretary, I created a resume and asked for the job. He said I could have it—I had proven I could fit in there, he said—but he could offer me only $7.25 an hour.

“You come from an unstable background,” Pastor Scott said. “You’ll have to prove your way out of that.”

I was stunned. He had said he believed in me. He knew about my professional background. Why would he, someone who made a living championing the homeless, offer me a job that wouldn’t allow me to afford to live?

Later, in fact-checking this article, I spoke with Pastor Scott, and he explained that he needed to hire “a very stable” secretary who was “able to work under a lot of pressure.” He wasn’t trying to be mean, he said.

Back then, I tried to convince him of my stability by explaining why I had “frozen” in my homelessness. “I was abused for a year straight,” I told him. “That’s why I broke down. And that’s why I’m here now.”

“But you were depressed and you hid,” Pastor Scott said. “You have been in our offices crying about what happened to you. We have given you a lot of support.”

In retrospect, it seems obvious why he responded the way he did—most of the people who helped me enjoyed how the relationship reinforced their sense of superiority over me. Sociologists call the dynamic “the gift relationship.”

Perhaps you have had to see a medical doctor who knows you desperately need what he or she has to offer, but who can barely be bothered to make eye contact with you. Meanwhile, you can sense that the doctor thinks you are stupid. But you need that person’s expertise, so you tolerate their behavior. This is what it feels like to be trapped inside the prison of a gift relationship. Except once you have been homeless, there is no door to walk out of.

It’s not a perfect comparison, because instead of money, the gift relationship trades in status and power. As Stern, the welfare historian, put it, “The giver was able to confirm his benevolence and the legitimacy of his position, while the poor were expected to understand their inferiority, the stigma attached to their position, and the docility and appreciation they should feel toward the giver.”

The seemingly kind pastor at the homeless aid organization offers me my first job in two years but twists the knife in my gut as he does.

That expectation that I prove myself was central to the exchange. After all, he had only so many gifts to hand out, so he must assess who is most deserving of them—that is the economic premise upon which the gift relationship rests.

He compares me to other people he might help and considers to whom he should extend his hand.

Of course, the construct isn’t new; it dates at least as far back to the Elizabethan poor laws, which were instituted to help those cut adrift by the end of feudalism. As the Industrial Revolution took hold, the notion of the “deserving poor” evolved and those whose circumstances were deemed pitiable or unavoidable enough to be worthy of charity received alms. The “undeserving poor” got prison, or worse. By the Victorian era, these categories of poor people had become enshrined.

Wrote Gareth Stedman Jones, author of Outcast London: “If he was unemployed, that was because he was not really interested in work; if he congregated together with others of his kind in poor areas, that was because he was attracted by the prospect of charitable hand-outs. It has sometimes been suggested that these attitudes require no explanation since all mid-Victorian social thinkers saw poverty as a product of character rather than of environment and therefore explained it in moral rather than economic terms.”

The reforms of the New Deal attempted to collapse those distinctions. But the Reagan administration brought them right back. The “able-bodied” were separated from those deemed officially “disabled,” and work requirements to receive welfare or food stamps became rampant. Reagan declared that homelessness would be solved if “every church and synagogue would take in 10 welfare families,” thus placing the responsibility on volunteers and do-gooders instead of the government.

But aid groups and individuals also had to make decisions about who was worthy of receiving their limited resources, and those decisions once again relied on the moral character of the recipient. Layer on top of that the fact that African Americans constitute 40 percent of the population experiencing homelessness today (but just 13 percent of the general population), and the morass of judgments and stereotypes only gets thicker.

For me, escaping the bondage of the gift relationship became the primary goal of my emergence.

At the first church I visited, a pastor picked me out of the crowd of unhoused people drifting in and out of the church because, as he said, “You were different. You were like a scared kitten, not like the rest of people grabbing and insisting on what they needed.”

In other words, my traumatized meekness worked in my favor.

Six months into my emergence, the transitional house shut down. I was still working for Street News, making about $400 a month, and had applied for numerous jobs, particularly in journalism, since I had worked at three major newspapers before my collapse: the Post-Standard in Syracuse, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and the Miami Herald.

But I had not worked as a full-time reporter in 22 years; I was 52. And there was the issue of my arrest record, which contained several citations for public lewdness, related to the times I had laid naked in the streets after having been sexually assaulted or been caught bathing in a stream. Before my homelessness, I had never been arrested.

No one responded to my resume. Market-rate rent was far beyond my reach, and the waiting list for government-subsidized housing was two years. I often woke up several times a night, my heart racing, my breathing shallow, as I worked my way out of a panic attack about having to return to the shelter.

At a job center, the idea came to contact one of my former editors, Frank, who had overseen my work at the Miami Herald’s magazine. To my surprise, he messaged me back immediately.

I asked if he could help me find the back issues that had my old clips. He couldn’t. But every so often, he texted or called me to ask how I was doing. The connection meant more than I can say. Every time I heard his voice, I remembered that I had been a professional journalist, that maybe I could be again.

My best bet to reenter journalism was to write about my homelessness, Frank said. From there, perhaps I could write a book. A few months later, he texted me about pitching my story to the Washington Post, where he had connections.

I had many hesitations about crafting a career out of my demise. I did not find the work “therapeutic,” something Frank and several editors since have insisted it would be. My reality proved otherwise: While the work provided me with a living wage, it continued to entrench me in the stereotypes and projections I was attempting to escape.

Regardless, knowing that I had one week to find a new place to live, I began working on the pitch.

Meanwhile, a self-help author I had met before my collapse, Byron Katie, was offering a one-day workshop at a nice hotel in Salt Lake City. There I met another participant, and that’s how, one Sunday evening, I found myself in the upscale city of Millcreek, Utah, in a poshly decorated home with stuffed furniture and a towering fig plant that reached from its clay pot to the skylight in the high-beamed ceiling. The women and men around me were middle and upper-middle class, all of them white. It was my first dinner invitation in more than two years. They had designated Sundays as a time when they would share whatever had come up during the week. The woman leading the group set a timer for five minutes per person.

I knew that someone there might be able to help me. I also knew that I had to toe that invisible line between socially acceptable need and helpless desperation, to be both perfect and unshakable in my demeanor. I knew there was little room for a display of emotion, however appropriate.

When the woman to my left finished speaking, I took a massive breath and told everyone what was happening in my life: that the transitional house was shutting down. That I had nowhere safe to go. That I didn’t want to go back to the homeless shelter or the park bench. That I was trying to trust and not completely freak out.

After I spoke, Susan, a professor at a nearby college, went into the bathroom to pray and ask Divine Guidance whether to help me.

The answer: “Help Lori.”

“How much can you afford?” she asked me when she returned.

I responded, “$300 to $400.”

She put me in her second home, which she was renting as an Airbnb, for two weeks, for free. She asked everyone she could think of if they would be willing to rent to me. When nothing came through, she prayed again.

Her answer: “Where there is heart room, there is house room.”

Susan took me to look at the spare bedroom in her bright yellow-brick home. We would share the kitchen, she said, where I was given one small cupboard to store my food. If what I had didn’t fit, she suggested I store it under my bed.

As “queen of the house,” she said, she would charge me $400 a month.

I had just accepted a part-time position as an $11-an-hour cashier at a Whole Foods—the store was not offering full-time work. So $400—$150 to $200 less than market-rate rents then—really was as much as I could afford.

Of course I took the room.

Susan told me she wanted to be like a big sister to me. Yet her discomfort with having me in her home was palpable.

“Initially, I was like, ‘I don’t want to do this,’” she told me when I asked why she had given me a place to stay. “‘I don’t want to! Noooo! Really? Do I have to?’”

Lori cooking dinner

Niki Chan Wiley

During the year and three months that we lived together, she tried to teach me about the wonder of heated wood floors, the importance of having a job, and the need to be frugal, a lesson her father had taught her, she told me.

She thought I was using far too much toilet tissue, and since she was paying for it, she said, she put a roll on the bathroom windowsill for her and another on the roller for me so we could track who would make whose last longest.

I told Susan that my father had been a microbiologist at nasa and built his own hardwood floors in the Eichler in which I grew up. And that, honestly, I had more toilet tissue in homelessness than I was feeling free to use in her home, so I would just splurge on my own wet wipes and tissues, thank you very much.

The tension between us grew. Susan told me she felt like she had to tiptoe around her own house. I told her that was my experience, too, that I felt like I had to be as small and as invisible as I possibly could.

When she outfitted my room with a brand-new twin bed from Costco, I complained that its rock-hard firmness made it difficult to sleep.

“I would have thought you would have been nothing but grateful,” she told me.

We had versions of this conversation repeatedly, and I told her I was grateful, but I was in pain and I had, after all, paid exactly what she’d asked.

Having a safe and secure home allowed me to stabilize. Despite the bed, I began to sleep soundly, to make friends, and to write more. Susan bought me $100 worth of clothes at a bargain store and urged me to apply for a credit card, which I did. She also introduced me to her neighbor, who sold me her 2004 Honda Accord without a deposit. I negotiated off the one debt I had before homelessness: a cellphone service I failed to cancel.

And in that year, the woman who’d given me the job at the transition home went to court with me and spoke to a judge about my character. About how my arrests had been the result of trauma. My record was erased.

I began to smile more, even sing to the tunes on the radio. But I never felt truly welcome in Susan’s home.

Typical roommate friction was freighted by the power differential. Once, I left rotten bananas on the kitchen counter. She responded by putting them in my bedroom.

“This is my house!” she screamed at me, by way of explanation.

“You’re a tyrant!” I screamed at her, my entire body shaking with the fear that my words would result in losing a roof over my head.

After our year was up, Susan told me she no longer wanted a roommate and extended my stay for the three months it took me to find a new place.

On the day I left her home, Susan skipped her yoga class to help me pack. As I lugged the last box to my car, she said something that I have found difficult to shake, but which she claims she can’t remember: “You were my project.”

Artwork by Anthony Gerace; Photography by Niki Chan Wiley

But I also paid rent, did chores, and thanked her profusely. Why should I act demure for being allowed to even rent a room? I will never allow myself to be diminished for that, as forever inside me is a memory of the dignity that my father instilled in me.

We were standing in the garden section of a store in Palo Alto. A white woman made some chitchat with my father about the plant he was holding. She asked him what he did for a living. He told her he was a microbiologist at nasa.

“You are a scientist,” she said, her voice increasing in both incredulousness and pitch. A Black man was a scientist? She didn’t need to say it.

I watched as my father—who had been denied housing and kicked off a bus bench by a police officer during the open racism of the Jim Crow era—stiffened his shoulders and lifted his head.

“Yes,” he said slowly, enunciating every syllable. “Imagine that.”

Rebuffed but speechless, the woman quickly walked away.

Just imagine, I have wanted to shout at so many people. I was homeless. And. Now. I. Am. Determined. To. Become. Something. Other. Than. Your. Project.

My first significant financial break came with the publication of my essay in the Washington Post—a door that Frank, my former editor, had opened.

I was awed by his assistance in reestablishing my career, but also so acutely aware of the imbalance of power in our relationship that I sometimes found myself unable to express my truth in our conversations. The most loaded of these exchanges occurred online, after I had posted on Facebook about wanting to open a nonprofit that housed women about to fall into homelessness—a sanctuary where I could offer others all that I had lost, complete with gardens and horses, a place where women could gather their wits and finances without having to endure what I did.

I was with a new friend, sitting on her couch and checking my messages, when I saw Frank’s:

“The grandiosity” of my post, he wrote, “might possibly be the beginning of a manic bi-polar episode.”

Is there a counselor you can talk to about this? he asked.

I can still feel the shame and confusion. I had confided in him about my experience of being held against my will and misdiagnosed. He’d said he believed in me—I’d thought he had.

“Steady,” my friend said. “If you come undone, you will give him reason to believe you are not stable. But if you can maintain your equanimity, then you will have really proved something.”

Pushing back my desire to tell Frank I was deeply hurt by his questioning of my sanity, I wrote back: “Thank you for your concern. But this is actually something that the life coach I am working with suggested.”

“It’s okay to have big dreams,” Frank responded.

I earned $5,000 from that story, enough to put my deposit down on that first apartment, as well as establish my first savings account in many years.

Later, Frank told me that he had questioned my mental state “just that one time,” and that he instantly overcame his doubt when I answered with such levelheadedness. He and I went on to lay the foundation of my memoir, and he continued to support my career by editing some of my pieces for free and introducing me to other editors.

Being a reporter allowed Lori to take control of her narrative

Niki Chan Wiley

But in between, we fought about the meaning of my book and the role he had in shaping it. I wanted to control my narrative and told him I felt endlessly judged by his continuous questioning of the decisions I had made in leaving the Herald and starting a business without any business experience. He said that “the role of an editor is to judge” and that the book was about my accountability to the reader—that I should acknowledge the poor decisions I had made and that had led to my demise. I needed to make those choices part of my story and not try to paint myself in only a positive light, he said.

He wanted me to offer fewer details about yanking my landlord from the fire because it made me look like I was openly patting myself on the back. But, on the other hand, he thought I should state exactly how much money my father had bequeathed me so that people could remember that. I felt strongly that if I was going to bare my soul about my collapse, I also had a right to be the hero in my own journey and share equally my successes.

“This book is about redemption,” Frank insisted.

But I was wary of proving and explaining myself, of crafting an entire life narrative around a demise. Why did I need to redeem myself to any audience?

For me, the purpose of the book was to help lessen the judgment that society has about collapse in the first place. Frank now says I misunderstood his reference to redemption, that it was about redeeming myself in my own eyes.

In the end, we parted amicably. I scrapped what I felt was turning into someone else’s version of my life.

For two years after emerging, the questioning surrounding my mental health continued. The most humiliating was having to visit a psychiatrist to keep my driver’s license, something I brought on myself when I first renewed it and answered truthfully that I had been institutionalized.

The shame is difficult to convey to someone whose sanity has never been officially questioned. Suffice it to say that it makes one feel doubted and, as a result, like an unwanted outlier.

My release from this questioning came when I took the annual form to a trauma-informed psychiatrist working with a nonprofit where I had been a grant writer for about a year. With his signature, I was free of being tracked by the dmv.

More personal relationships were a different matter.

While living with Susan, I had hired a life coach, a woman whom I had known before my collapse. She’d met me when I was successful, when I had lots of money in the bank, a house, and a horse. So I thought she would serve as a powerful reminder of the success I could achieve again. But she was not sympathetic to my homelessness. In fact, she was shocked.

“You of all people,” she told me. “I never would have expected it.”

When I was writing my Washington Post story and asked if she would talk to their fact-checkers, she said yes. But when they called, she made it clear she wasn’t interested in participating. I took this as an indication that she didn’t want to stand up for me publicly, and when I confronted her about it, she didn’t deny it.

Another clue was her response to my muteness in the psych wards.

“People expect people to talk,” she quipped when I complained about how traumatized I felt about their debilitating misdiagnoses.

When I told her how I complained to my department manager at Whole Foods after he insisted that I take a preset timer on a restroom break, she said, “People don’t exactly want to hear the opinion of someone who has just been homeless.”

She apologized for that remark, calling herself “an asshole.” But it took time for me to realize that she couldn’t come to terms with my collapse without continually shaming me for it.

After about a year, I left her and began seeing the director of mental health services at Fourth Street Clinic, a nonprofit that specializes in working with low-wage earners and unhoused people.

There, Jamie Bustamante, the mental health clinic director, and I worked together once a week for a year and a half.

In addition to talk therapy, we used a specialized trauma treatment through which I worked to release the memories of John’s assaults as well as gain a greater compassion for myself. And in the process, Bustamante came to a very different diagnosis about my mental health:

“You have post-traumatic stress disorder, but you have not displayed any of the symptoms of any mental illness that the hospital diagnosed you with,” she told me.

Bustamante went into my hospital records and changed my diagnosis to PTSD, a far cry from the lifelong mental illnesses for which I was forced to take court-ordered drugs.

The nightmares about my time locked up in those psych wards have lessened, though they have not totally gone away. I doubt they ever will.

Last spring, I was in downtown Salt Lake City, reporting a story for the Washington Post about a young woman, Dawn, who had escaped homelessness via a $9-an-hour job supervising a port-a-potty for the unhoused. Her station was across the street from a youth shelter. It took days for those youth to trust me enough to tell me their stories. But once they did and I told them about my past, a tall, thin young man asked, “Ms. Lori, how did you make it out of homelessness?”

He was trying to get a job at a shoe store, he said, and wasn’t sure he was going to get it, as he needed a letter of recommendation from his parole officer. His soft brown eyes burned with self-doubt.

I remembered an interview I had in 2018 with Terry Kupers, a professor emeritus at the Wright Institute Graduate School of Psychology and author of the books Prison Madnessand Solitary: The Inside Story of Supermax Isolation and How We Can Abolish It.

“The people who emerge from deep collapse and go on to thrive in mainstream life are the outliers,” Kupers had told me. “They grasp the social inequity of their circumstances and don’t blame just themselves for what went wrong in their lives. Therefore they are more assertive and less vulnerable to shame.”

Those words rang so true. I looked at the young man standing in front of me.

“By refusing to believe anything bad anyone said about me,” I told him unequivocally.

I could tell my words resonated. He nodded confidently, said goodbye, and walked into the shelter for the night.

Often, when I share my perspective on how the systems to address homelessness are broken, people ask me what I think the solutions are. That’s when I refer back to Hübl, the spiritual teacher who refers to homelessness as a “strong trauma symptom.”

How can we, as a society, address that level of pain? I asked him.

First, we need to take a giant, collective pause, so we can feel, Hübl said, because only in this pause will we understand how to truly respond.

“If I see a homeless person, either I become a bit numb and shut that person out or I let myself be informed. Allowing myself to be informed does not mean looking for immediate actions that will ‘fix’ the person or situation. If I do that, looking for the solution is avoiding the process. The solution comes from creating a relationship in the moment—to let myself feel what it feels like to be in the presence of someone who lives on the street.”

Only then can we begin to address what people experiencing homelessness really need.

Making my way through your debilitating projections on the unhoused has felt like trying to run underwater with weights on my ankles. No, I have never been addicted to any kind of drug, I told you, showing you my bloodwork records from homelessness to prove it. No, I didn’t have a “relationship” with John.

In all this proving, when I gasped for air, expressing my exhaustion and pain with you, you often answered, “Why do you care what I think?”

To which I wanted to scream, “How privileged of you.”

And no, that doesn’t mean I’m not thankful for your assistance in my emergence. Thank you for giving me the necessities I needed to save my life. Nearly five years after leaving my park bench, I’ve become a trauma-aware journalist. After three years of freelancing I am the national housing crisis reporter for the Economic Hardship Reporting Project and write a monthly column for Defector called How Are You Coping With That? For me, it is a way to flip the paradigm, to ask people in harsh circumstances about their resilience, as opposed to their assumed weaknesses.

So keep helping in whatever ways you can.

Still, nearly five years into this long and complicated journey, I have one last thing I need from you.

While you stand in your place in the accepted social hierarchy of giving and receiving, looking down on those you deem worthy of “helping,” would you please stop to notice how you are slapping us in the face with the very hand that you have extended in your goodwill?

This story was written in partnership with the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.