As one who was identified in the 1960s with the popularization of a literary genre known best as the New Journalism—an innovation of uncertain origin that appeared prominently in Esquire, Harper’s, The New Yorker, and other magazines, and was practiced by such writers as Norman Mailer and Lillian Ross, John McPhee, Tom Wolfe, and the late Truman Capote—I now find myself cheerlessly conceding that those impressive pieces of the past (exhaustively researched, creatively organized, distinctive in style and attitude) are now increasingly rare, victimized in part by the reluctance of today’s magazine editors to subsidize the escalating financial cost of such efforts, and diminished also by the inclination of so many younger magazine writers to save time and energy by conducting interviews with the use of that expedient but somewhat benumbing literary device, the tape recorder.

I myself have been interviewed by writers carrying recorders, and as I sit answering their questions, I see them half-listening, nodding pleasantly, and relaxing in the knowledge that the little wheels are rolling. But what they are getting from me (and I assume from other people they talk to) is not the insight that comes from deep probing and perceptive analysis and old-fashioned legwork; it is rather the first-draft drift of my mind, a once-over-lightly dialogue that— while perhaps symptomatic of a society permeated by fast-food computerized bottom-line impersonalized workmanship—too frequently reduces the once artful craft of magazine writing to the level of talk radio on paper.

Far from decrying this trend, most editors tacitly approve of it, because a taped interview that is faithfully transcribed can protect the periodical from those interviewees who might later claim that they had been damagingly misquoted—accusations that, in these times of impulsive litigation and soaring legal fees, cause much anxiety, and sometimes timidity, among even the most independent and courageous of editors.

Another reason editors are accepting of the tape recorder is that it enables them to obtain publishable articles from the influx of facile freelancers at pay rates below what would be expected and deserved by writers of more deliberation and commitment. With one or two interviews and a few hours of tape, a relatively inexperienced journalist today can produce a 3,000-word article that relies heavily on direct quotation and (depending largely on the promotional value of the subject at the newsstand) will gain a writer’s fee of anywhere from approximately $500 to slightly more than $2,000—which is fair payment, considering the time and skill involved, but it is less than what was being paid for articles of similar length and topicality when I began writing for some of these same magazines more than a quarter of a century ago.

In those days, however, the contemporary writers I admired usually devoted weeks and months to research and organization, writing and rewriting, before our articles were considered worthy of occupying the magazine space that today is filled by many of our successors in one tenth the time. And in the past, too, magazines seemed more liberal than now about research expenses.

During the winter of 1965 I recall being sent to Los Angeles by Esquire for an interview with Frank Sinatra, which the singer’s publicist had arranged earlier with the magazine’s editor. But after I had checked into the Beverly Wilshire, had reserved a rental car in the hotel garage, and had spent the evening of my arrival in a spacious room digesting a thick pack of background material on Sinatra, along with an equally thick steak accompanied by a fine bottle of California burgundy, I received a call from Sinatra’s office saying that my scheduled interview the next afternoon would not take place.

Mr. Sinatra was very upset by the latest headlines in the press about his alleged Mafia connections, the caller explained, adding that Mr. Sinatra was also suffering from a head cold that threatened to postpone a recording date later in the week at a studio where I had hoped to observe the singer at work. Perhaps when Mr. Sinatra was feeling better, the caller went on, and perhaps if I would also submit my interview to the Sinatra office prior to its publication in Esquire, an interview could be rescheduled.

After commiserating about Mr. Sinatra’s cold and the news items about the Mafia, I politely explained that I was obliged to honor my editor’s right to being the first judge of my work; but I did ask if I might telephone the Sinatra office later in the week on the chance that his health and spirits might then be so improved that he would grant me a brief visit. I could call, Sinatra’s representative said, but he could promise nothing.

For the rest of the week, after apprising Harold Hayes, the Esquire editor, of the situation, I arranged to interview a few actors and musicians, studio executives and record producers, restaurant owners and female acquaintances who had known Sinatra in one way or another through the years. From most of these people, I got something: a tiny nugget of information here, a bit of color there, small pieces for a large mosaic that I hoped would reflect the man who for decades had commanded the spotlight and had cast long shadows across the fickle industry of entertainment and the American consciousness.

As I proceeded with my interviews—taking people out each day to lunch and dinner while amassing expenses that, including my hotel room and car, exceeded $1,300 after the first week—I rarely, if ever, removed a pen and pad from my pocket, and I certainly would not have considered using a tape recorder had I owned one. To have done so would have possibly inhibited these individuals’ candor, or would have otherwise altered the relaxed, trusting, and forthcoming atmosphere that I believe was encouraged by my seemingly less assiduous research manner and the promise that, however retentive I considered my memory to be, I would not identifiably attribute or quote anything told me without first checking back with the source for confirmation and clarification.

Quoting people verbatim, to be sure, has rarely blended well with my narrative style of writing or with my wish to observe and describe people actively engaged in ordinary but revealing situations rather than to confine them to a room and present them in the passive posture of a monologist. Since my earliest days in journalism, I was far less interested in the exact words that came out of people’s mouths than in the essence of their meaning. More important than what people say is what they think, even though the latter may initially be difficult for them to articulate and may require much pondering and reworking within the interviewee’s mind—which is what I gently try to prod and stimulate as I query, interrelate, and identify with my subjects as I personally accompany them whenever possible, be it on their errands, their appointments, their aimless peregrinations before dinner or after work. Wherever it is, I try physically to be there in my role as a curious confidant, a trustworthy fellow traveler searching into their interior, seeking to discover, clarify, and finally to describe in words (my words) what they personify and how they think.

There are times, however, when I do take notes. Occasionally there is a remark that one hears—a turn of phrase, a special word, a personal revelation conveyed in an inimitable style that should be put on paper at once lest part of it be forgotten. That is when I may take out a notepad and say, “That’s wonderful! Let me get that down just as you said it”; and the person, usually flattered, not only repeats it but expands upon it. On such occasions there can emerge a heightened spirit of cooperation, almost of collaboration, as the person interviewed recognizes that he has contributed something that the writer appreciates to the point of wanting to preserve it in print.

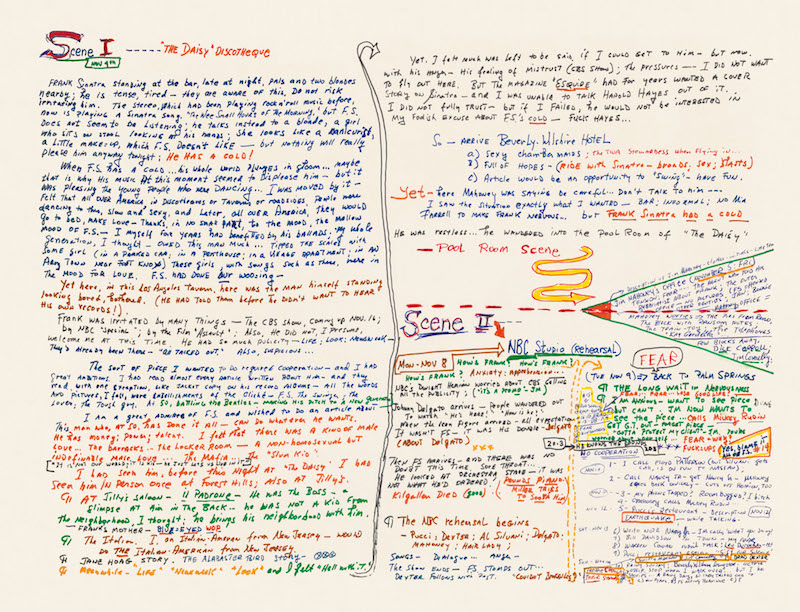

Gay Talese’s outline for “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” sketched on one of his trademark shirt boards, 1966. © 2015 and courtesy of Gay Talese.

Gay Talese’s outline for “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” sketched on one of his trademark shirt boards, 1966. © 2015 and courtesy of Gay Talese.

At other times I make notes unobserved by the interviewee—such as during those interruptions in our talks when the person has temporarily left the room, thus allowing me moments in which to jot down what I believe to be the relevant parts of our conversation. I also occasionally make notes immediately after the interview is completed, when things are still very fresh in mind. Then, later in the evening, before I go to bed, I sit at my typewriter and describe in detail (sometimes filling four or five pages, single-spaced) my recollections of what I had seen and heard that day—a chronicle to which I constantly add pages with each passing day of the entire period of research.

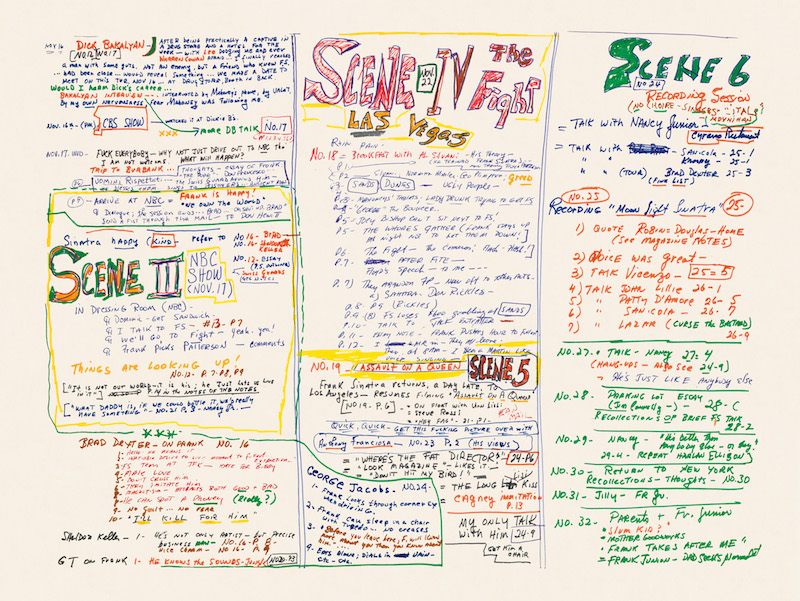

Gay Talese’s outline for “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” sketched on one of his trademark shirt boards, 1966. © 2015 and courtesy of Gay Talese.

Gay Talese’s outline for “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” sketched on one of his trademark shirt boards, 1966. © 2015 and courtesy of Gay Talese.

This chronicle is kept in an ever-expanding series of cardboard folders containing such data as the places where I and my sources had breakfast, lunch, and dinner (restaurant receipts enclosed to document my expenses); the exact time, length, locale, and subject matter of every interview; together with the agreed-upon conditions of each meeting (i.e., am I free to identify the source, or am I obliged to contact that individual later for clarification and/or clearance?). And the pages of the chronicle also include my personal impressions of the people I interviewed, their mannerisms and physical description, my assessment of their credibility, and much about my own private feelings and concerns as I work my way through each day—an intimate addendum that now, after nearly 30 years of habit, is of use to a somewhat autobiographical book I am writing; but the original intent of such admissive writing was self-clarification, reaffirming my own voice on paper after hours of concentrated listening to others, and also, not infrequently, the venting of some of the frustration felt when my research appeared to be going badly, as it certainly did in the winter of 1965 when I was unable to meet face to face with Frank Sinatra.

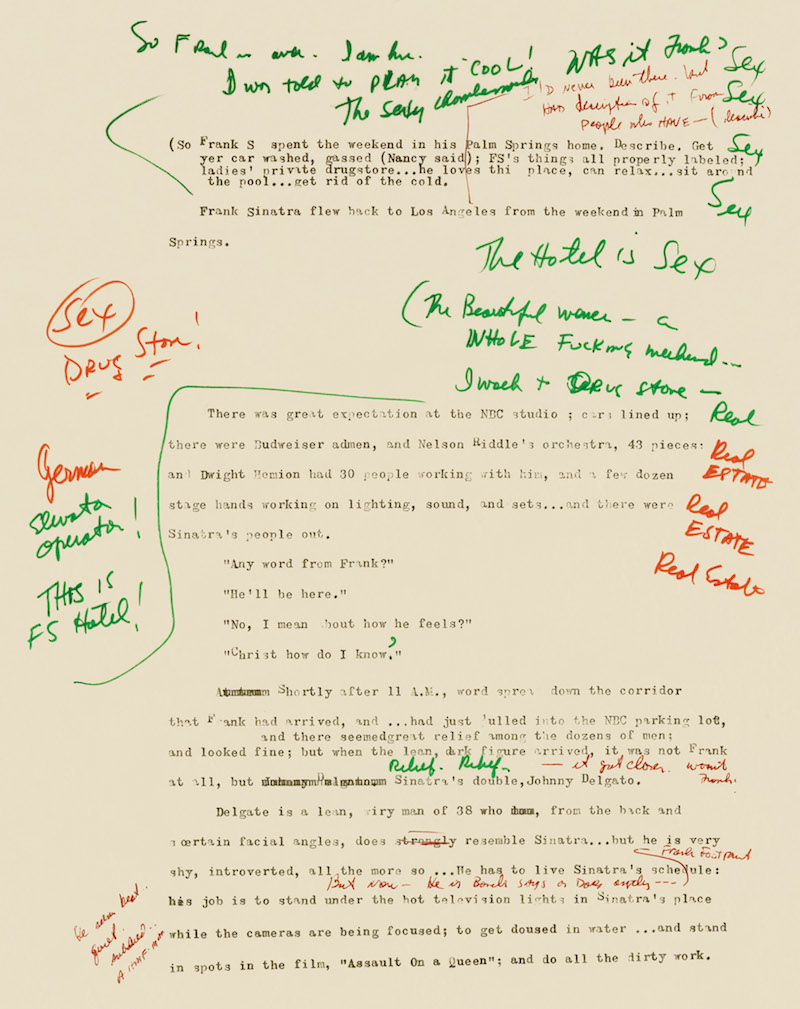

A page from the first draft of the Sinatra piece, which Talese views as “really the fast typing of my notes… filled with typos, misspellings, and scribblings between the typed lines revealing lots of frustration and lack of direction.” © 2015 and courtesy of Gay Talese.

A page from the first draft of the Sinatra piece, which Talese views as “really the fast typing of my notes… filled with typos, misspellings, and scribblings between the typed lines revealing lots of frustration and lack of direction.” © 2015 and courtesy of Gay Talese.

After trying without success to reschedule the Sinatra interview during my second week in Los Angeles (I was told that he still had a cold), I continued to meet with people who were variously employed in some of Sinatra’s many business enterprises—his record company, his film company, his real estate operation, his missile parts firm, his airplane hangar—and I also saw people who were more personally associated with the singer, such as his overshadowed son, his favorite haberdasher in Beverly Hills, one of his bodyguards (an ex–pro lineman), and a little gray-haired lady who traveled with Sinatra around the country on concert tours, carrying in a satchel his 60 hairpieces.

From such people I collected an assortment of facts and comments, but what I gained at first from these interviews was no particular insight or eloquent summation of Sinatra’s stature; it was rather the awareness that so many of these people, who lived and worked in so many separate places, were united in the knowledge that Frank Sinatra had a cold. When I would allude to this in conversations, citing it as the reason my interview with him was being postponed, they would nod and say yes, they were aware of his cold, and they also knew from their contacts within Sinatra’s inner circle that he was a most difficult man to be around when his throat was sore and his nose was running. Some of the musicians and studio technicians were delayed from working in his recording studio because of the cold, while others among his personal staff of 75 were not only sensitive to the effects of his ailment but they revealed examples of how volatile and short-tempered he had been all week because he was unable to meet his singing standards. And one evening in my hotel, I wrote in the chronicle:

…it is a few nights before Sinatra’s recording session, but his voice is weak, sore and uncertain. Sinatra is ill. He is a victim of an ailment so common that most people would consider it trivial. But when it gets to Sinatra it can plunge him into a state of anguish, deep depression, panic, even rage. Frank Sinatra has a cold. Sinatra with a cold is Picasso without paint, Ferrari without fuel—only worse. For the common cold robs Sinatra of that uninsurable jewel, his voice, cutting into the core of his confidence, and it affects not only his own psyche but also seems to cause a kind of psychosomatic nasal drip within dozens of people who work for him, drink with him, love him, depend on him for their own welfare and stability.

A Sinatra with a cold can, in a small way, send vibrations through the entertainment industry and beyond as surely as a President of the United States, suddenly sick, can shake the national economy…

The next morning I received a call from Frank Sinatra’s public relations director.

“I hear you’re all over town seeing Frank’s friends, taking Frank’s friends to dinner,” he began, almost accusingly.

“I’m working,” I said. “How’s Frank’s cold?” (We were suddenly on a familiar basis.)

“Much better, but he still won’t talk to you. But you can come with me tomorrow afternoon to a television taping if you’d like. Frank’s going to try to tape part of his NBC special… Be outside your hotel at three. I’ll pick you up.”

I suspected that Sinatra’s publicist wanted to keep a closer eye on me, but I was nonetheless pleased to be invited to the taping of the first segment of the one-hour special that NBC-TV was scheduled to air in two weeks, entitled “Sinatra—The Man and His Music.”

On the following afternoon, promptly and politely, I was picked up in a Mercedes convertible driven by Sinatra’s dapper publicist, a square-jawed man with reddish hair and a deep tan who wore a three-piece gabardine suit that I favorably commented upon soon after getting into the car—prompting him to acknowledge, with a certain satisfaction, that he had obtained it at a special price from Frank’s favorite haberdasher. As we drove, our conversation remained amiably centered around such subjects as clothes, sports, and the weather until we arrived at the NBC building and pulled into a white concrete parking lot in which there were about 30 other Mercedes convertibles as well as a number of limousines in which were slumped black-capped drivers trying to sleep.

Entering the building, I followed the publicist through a corridor into an enormous studio dominated by a white stage and white walls and dozens of lamps and lights dangling everywhere I looked. The place resembled a gigantic operating room. Gathered in one corner of the room behind the stage, awaiting the appearance of Sinatra, were about one hundred people—camera crews, technical advisers, Budweiser admen, attractive young women, Sinatra’s bodyguards and hangers-on, and also the director of the show, a sandy-haired, cordial man named Dwight Hemion, whom I had known from New York because we had daughters who were preschool playmates. As I stood chatting with Hemion, and overhearing conversations all around me, and listening to the 43 musicians, sitting in tuxedos on the bandstand, warming up their instruments, my mind was racing with ideas and impressions; and I would have liked to have taken out my notepad for a second or two. But I knew better.

And yet after two hours in the studio—during which time Sinatra’s publicist never left my side, even when I went to the bathroom—I was able to recall later that night precise details about what I had seen and heard at the taping; and in my hotel I wrote in the chronicle:

Frank finally arrived on stage, wearing a high-necked yellow pullover, and even from my distant vantage point his face looked pale, his eyes seemed watery. He cleared his throat a few times.

Then the musicians, who had been sitting stiffly and silently in their seats ever since Frank had joined them on the platform, began to play the opening song, “Don’t Worry about Me.” Then Frank sang through the whole song—a rehearsal prior to taping—and his voice sounded fine to me, and it apparently sounded fine to him, too, because after the rehearsal he suddenly wanted to get it on tape.

He looked up toward the director, Dwight Hemion, who sat in the glass-enclosed control booth overlooking the stage, and he yelled: “Why don’t we tape this mother?”

Some people laughed in the background, and Frank stood there tapping a foot, waiting for some response from Hemion.

“Why don’t we tape this mother?” Sinatra repeated, louder, but Hemion just sat up there with his headset around his ears, flanked by other men also wearing headsets, staring down at a table of knobs or something. Frank stood fidgeting on the white stage, glaring up at the booth, and finally the production stage manager—a man who stood to the left of Sinatra, and also wore a headset—repeated Frank’s words exactly into his line to the control room: “Why don’t we tape this mother?”

Maybe Hemion’s switch was off up there, I don’t know, and it was hard to see Hemion’s face because of the obscuring reflections the lights made against the glass booth. But by this time Sinatra is clutching and stretching his yellow pullover out of shape and screaming up at Hemion: “Why don’t we put on a coat and tie, and tape this… ”

“Okay, Frank,” Hemion cut in calmly, having apparently not been plugged into Sinatra’s tantrum, “would you mind going back over … ”

“Yes I would mind going back!” Sinatra snapped. “When we stop doing things around here the way we did them in 1950 maybe we…”

…Although Dwight Hemion later managed to calm Sinatra down, and in time to successfully tape the first song and a few others, Sinatra’s voice became increasingly raspy as the show progressed—and on two occasions it cracked completely, causing Sinatra such anguish that in a fitful moment he decided to scrub the whole day’s session. “Forget it, just forget it!” he told Hemion. “You’re wasting your time. What you got there,” he continued, nodding to the singing image of himself on the TV monitor, “is a man with a cold.”

There was hardly a sound heard in the studio for a moment or two, except for the clacking heels of Sinatra as he left the stage and disappeared. Then the musicians put aside their instruments, and everybody else slowly turned toward the exit… In the car, coming back to the hotel, Frank’s publicist said they’d try to retape the show within the week, he’d let me know when. He also said that in a few weeks he was going to Las Vegas for the Patterson–Clay heavyweight fight (Frank & friends would be there to watch it), and if I wanted to go he’d book me a room at the Sands and we could fly together. Sure, I said… but to myself I’m thinking: how long will Esquire continue to pay my expenses? By the end of this week, I’ll have spent more than $3,000, have not yet talked to Sinatra, and, at the rate we’re going, it’s possible I never will…

Before going to bed that night, I telephoned Harold Hayes in New York, briefed him on all that was happening and not happening, and expressed concern about the expenses.

“Don’t worry about the expenses as long as you’re getting something out there,” he said. “Are you getting something?”

“I’m getting something,” I said, “but I don’t exactly know what it is.”

“Then stay out there until you find out.”

I stayed another three weeks, ran up expenses close to $5,000, returned to New York, and then took another six weeks to organize and write a 55-page article that was largely drawn from a 200-page chronicle that represented interviews with more than 100 people and described Sinatra in such places as a bar in Beverly Hills (where he got into a fight), a casino in Las Vegas (where he lost a small fortune at blackjack), and the NBC studio in Burbank (where, after recovering from the cold, he retaped the show and sang beautifully).

As time-consuming and financially costly as it was, it was this research that marked my Sinatra piece and dozens of other magazine articles that I published during the 1960s.

The Esquire editors titled the piece “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” and it appeared in the April 1966 issue. It remains in print today in a Dell paperback collection of mine called Fame and Obscurity. While I was never given the opportunity to sit down and speak alone with Frank Sinatra, this fact is perhaps one of the strengths of the article. What could he or would he have said (being among the most guarded of public figures) that would have revealed him better than an observing writer watching him in action, seeing him in stressful situations, listening and lingering along the sidelines of his life?

This method of lingering and careful listening and describing scenes that offer insight into the individual’s character and personality—a method that a generation ago came to be called the New Journalism—was, at its best, really fortified by the “Old Journalism’s” principles of tireless legwork and fidelity to factual accuracy. As time-consuming and financially costly as it was, it was this research that marked my Sinatra piece and dozens of other magazine articles that I published during the 1960s—and there were other writers during this period who were doing even more research than I was, particularly at The New Yorker, one of the few publications that could afford, and today still chooses to afford, the high cost of sending writers out on the road and allowing them whatever time it takes to write with depth and understanding about people and places. Among the writers of my generation at The New Yorker who personify this dedication to roadwork are Calvin Trillin and the aforementioned John McPhee; and the most recent example of it at Esquire was the piece about the former baseball star Ted Williams, written by Richard Ben Cramer, an old-fashioned legman of 36 whose keen capacity to listen has obviously not been dulled or otherwise corrupted by the plastic ear of a tape recorder.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Frank Sinatra Has a Cold. Used with the permission of the publisher, Taschen. Copyright © 2021 by Gay Talese.